Building an Exceptional Team: The Foundation of Scaling Success

April 2007, Ramallah. Our Trojan horse was stationed near Amin Lubada’s house. He’s a notorious terrorist, wanted for years for masterminding seven bombings that injured and killed dozens of innocent people. There we were, twelve elite commandos in the IDF, immersed in the silence and total darkness of a windowless truck, in the heart of extremely

dangerous territory. It was 3:00 A.M, and the adrenaline was at its peak. We were waiting for the agreed upon signal. Under the pressure, our brains were reviewing all possible scenarios one last time.

Pow, pow, pow!

The back door opened violently, and we tumbled out of the undercover car. A dozen well-trained fighters. We split into four distinct task forces and sprinted into position, a well-established strategy to flush out one of the most dangerous terrorists in the Middle East without collateral damage. Another long silence.

Bam, bam, bam, bam!

A burst of bullets was fired. A projectile passed right over my head and that of Elisha, a longtime teammate in the elite Unit 217. We located the origin of the shot and repositioned ourselves, taking cover in a blind spot. We returned fire and signaled to the task force stationed on a roof overlooking the scene. In no time at all, Amin Lubada was neutralized. Mission accomplished.

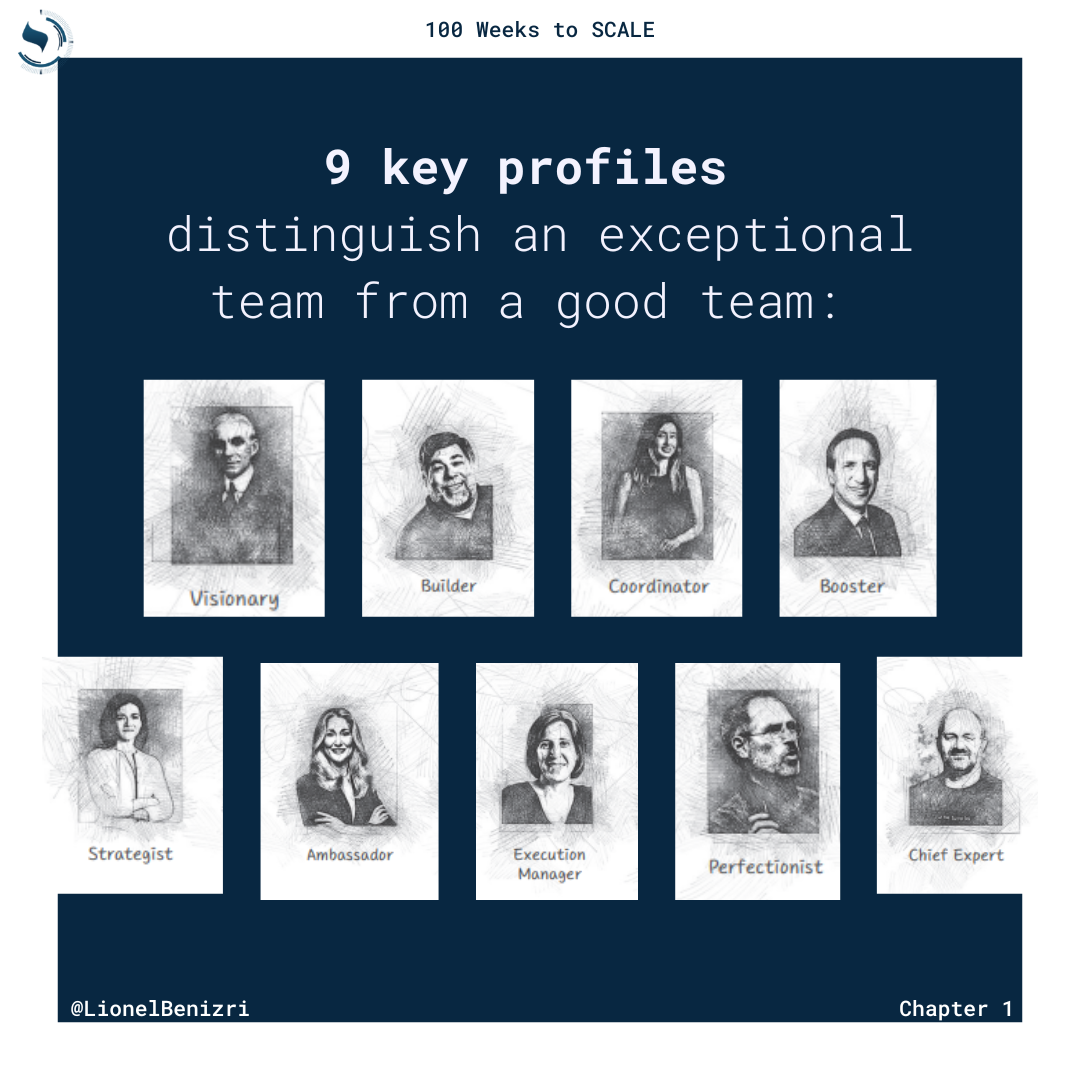

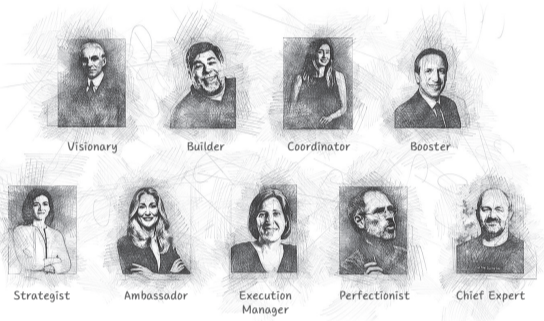

Exceptional Challenges Require An Exceptional Team

In the years since this operation and dozens of others that followed, I’ve had the opportunity to analyze the efficiency of many teams in different environments. Whatever their missions – launching a startup, scaling up mature companies, or carrying out a difficult operation in enemy territory – they all had one common denominator. When faced with risk, teams can only succeed if they include certain key profiles. When one of them is missing, the entire endeavor is at risk. Scaling up is an exceptional challenge and therefore requires not only efficient but also particularly complementary teammates. Here are the nine key profiles that, in my experience, make all the difference between a good team and an exceptional team.

1. The Visionary – Imagines the Concept

You know this profile well. Like Henry Ford or Steve Jobs, this leader is able to galvanize a team around a clear long-term vision. Creative, often a business thinker, he is driven by the burning desire to have an impact on the society of tomorrow. This person is farsighted and imagines the product or service likely to carry the initial vision forward. His credibility will be directly proportional to his ability to carry out each of the steps required to complete the project. Henry Ford left humanity with a unique industrial concept leading to scalable production in the automotive industry. Steve Jobs, on the other hand, was the forerunner of technological ubiquity.

Visionaries are usually the founders of companies. Those who also combine leadership, composure, charisma, and organizational skills usually play the additional role of CEO.

2. The Builder – Designs the Product

Leonardo da Vinci was an incredible visionary, the father of civil and military mobility. He lacked the presence of one key profile at his side to turn his concepts into reality. Hundreds of years before their time, he imagined and tried to prototype models of airplanes, tanks, parachutes, and even drones. But none of these machines ever became a product sold on the Venetian market. The builder is there to ensure this essential step: transforming a vision into a finished product.

This is the role Steve Wozniak brilliantly played alongside Steve Jobs in the early ‘80s. With the construction of the Apple I and Apple II, he turned a tiny startup of three people crammed in a garage into a phenomenal industrial success. These product builders often have strong problem-solving skills and are instrumental in developing innovative products.

3. The Coordinator – Achieves Product-Market Fit

The launch of our first startup ended in failure. The second, however, kept its promises. One notable difference between the two enterprises was the presence of a coordinator. In our first entrepreneurial odyssey, we managed to transform our vision into a tangible product, a mobile knowledge management application. But the sequel was cut short by a lack of coordination between customer requests and the features developed. We failed to achieve the all-important product-market fit.

The coordinator is like a midfielder who acts as the link between defense and offense in soccer. He ensures that what is delivered is always perfectly in line with what customers want, even if their requests change. To be effective, he must be a good listener, be able to translate customer needs into technical adjustments, and ensure good operational follow-up.

4. The Booster – Builds a Sales Machine at Scale

The visionary provides the vision, the builder builds the product, and the coordinator ensures the product always fits customer requests. This embryonic success still needs to be scaled up. This is precisely the mission of the booster.

In the early ‘70s, a now-famous coffeehouse chain had only three locations in the city of Seattle. Its concept was based on the importing of high-quality coffee beans, produced by a Dutch roaster, and customers loved this premium coffee. But the chain struggled to grow. It stalled with six locations for about fifteen years. And then, in 1987, it took off. That year, Howard Schultz took the reins of Starbucks to turn it into an industrial empire that today operates more than thirty thousand locations for fifty million daily visitors.

This example perfectly sums up the importance of the booster in deploying a small business’s products on a large scale. But this principle is still valid for medium-sized companies which, when scaling up, have no choice but to acquire a bulldozer profile capable of making sales skyrocket. The booster is often the VP of Sales.

5. The Strategist – Pilot to the Future

The strategist is a missing profile in many organizations. He is the architect of strategic projects. He is proactive and has strong analytical skills. His impact on setting objectives, measuring performance, targeting priorities, and anticipating market trends likely to affect the company’s future performance is decisive.

In 2008, a company specializing in social networking enjoyed increasing traffic but also generated huge losses ($130 million in 2007), due to the lack of an efficient operational structure and a profitable business model. Luckily, during a Christmas party, the young founder met a formidable strategist and master in the art of scaling. Three months later, Sheryl Sandberg took her place alongside Mark Zuckerberg to triple Facebook’s profits and quintuple its valuation in just three and a half years.

So, to build our exceptional team, we must create a new position, that of Chief Scale Officer, mandated by the board to work, not in place of but alongside the Founder. Do you have this key profile in your ranks?

6. The Ambassador – Increases the Visibility of the Company

The five previous profiles are literally indispensable. Ideally, this initial team is complemented by the ambassador. The latter is in charge of concluding as many partnerships as possible, developing the company’s address book, and above all creating, establishing, and then increasing brand awareness. Perfectly embodied by Tifani Bova at Salesforce or Nancy Kramer at IBM, the role of brand ambassador, or chief evangelist, has grown considerably in recent years.

In 2012, a very small Australian company called Canva had only twenty employees. Guy Kawasaki was appointed Chief Evangelist. He contributed to the rapid increase in the company’s fame, helping it to grow exponentially from twenty to two hundred employees in four years. Its valuation increased tenfold. It’s hard not to be convinced by such figures.

7. The Execution Manager – Runs the Operation

In the middle of a shooting range, somewhere in the Middle East, an instructor asked one of my friends who had just assisted me in an urban combat exercise, “What’s the name of Napoleon’s lieutenant?”

When he got no response, he continued, “You see, no one ever remembers the number twos.”

This conclusion is so far from reality that we laughed. In the daily life of a commando, whether an intelligence agent or an entrepreneur, there is one inescapable principle: you cannot accomplish anything alone. The CEO who does every job is a myth.

Without its extraordinary number two, Sergei Brin and Larry Page’s Google would never have become a unicorn. Susan Wojcicki aptly dubbed “the most important Googler ever hired,” organizes everything there. Pure and simple. From technical operations to business presentations, the execution manager implements the strategy of the strategist. She usually occupies the position of COO (Chief Operating Officer).

8. The Perfectionist – Refines and Improves Deliverables

Many leaders are satisfied and take pride in having several, if not all of the above profiles on their team. That’s fair. Armed with a demand-driven product, a differentiation strategy, and an operational machine, they are already generating results that command respect.

This is the case with a company I was coaching in early 2018. The manager wanted to start a scale process, but it seemed that something was hampering the quality of production and the work of the sales teams. One Friday morning, during a leadership seminar, I invited them to think about the problems they wanted to solve and to articulate them clearly. They all expressed their frustration:

“The datasets we provide often contain errors.”

“Our sales and marketing materials are never perfect.” Etc.

The situation became crystal clear: they lacked one essential profile, the perfectionist.

Steve Jobs embodied this profile to perfection when he made his comeback at Apple in 1997. He ensured that each component fit seamlessly into the sleek and stylish design of iPods and iPhones. Whether it’s controlling the quality of a product in all its aspects or refining a commercial deliverable, the perfectionist is essential for generating excellence where competitors settle for very good.

9. The Expert – Brings Technical Expertise

The last profile is that of the chief expert.

On this subject, I remember an anecdote that occurred when I was still a young entrepreneur. I can see myself going to the most prestigious law firms to present a documentation software that we had created. Our prospective clients listened, looking interested. Some associates invited us back to explore the possibility of a pilot test while others decided not to proceed beyond our first exchange. Yet, the pitch and the level of preparation were the same for each meeting. But each time, the participation or absence of a single per- son made all the difference. For us, it was Ittai Artzi, a former head of the intelligence services’ technology department. He has indisputable expertise in his field and because of this, exudes a natural authority with our clients.

Without going too far, this is the function of a Chief Technology Officer (CTO) in a technology company. A tenor in his field. Over the past few years, I’ve had the chance to team up with this profile. It’s largely because of his level of expertise that we were able to gain the trust of renowned companies, where our competitors deployed many more resources. People in this profile, who are passionate about their field, have a decisive impact on the credibility of an organization.

How Do We Proceed Concretely?

Three questions were often raised when I presented this model to the hundreds, if not thousands, of entrepreneurs, consultants, and board members of mid-sized companies that I met.

The first question is systematic. It’s the issue of people with multiple roles. There are indeed many organizations in which the founder (visionary profile) also plays the role of sales booster, strategist, or even chief expert. This is a disaster. Chasing two deer at once is a bad hunting strategy. It’s just as bad on an entrepreneurial level. In these organizations, an executive wearing several hats never manages to perform well on multiple simultaneous projects during the same quarter. This makes sense if we recall the characteristic of efficient organizations: by definition, each role, each position, each profile is evaluated by one indicator and aims at one objective, both of which are unique to it.

The second question concerns the order in which to recruit profiles. This order is based on the model itself. Indeed, it is thought that the success of a startup can be broken down into three phases. The first objective is to obtain the concrete use of a new product by the target users. This phase, known as the product-market fit, necessarily requires a concept imagined by the visionary, a product developed by a builder, and the matching of product to customerrequests ensured by the coordinator. There’s no need to expand the team before the completion of this first phase.

The next phase is structuring the business model (the strategist’s role) and establishing a large-scale reproducible sales machine (the booster’s work). Finally, the last phase sees the advent of a company strengthened by brand awareness (cultivated by the ambassador) and optimal organizational processes (driven by the execution manager) to maximize productivity. The expansion of the scale team follows the same trend.

The third dilemma facing many growing companies is how to fulfill these complementary roles when the company’s funds in the expansion phase don’t yet allow it to recruit these nine key profiles. There are several solutions. In times of budget constraints, it’s undoubtedly best to ensure that everyone wears only one hat at a time in order to properly manage a single project before embarking on any other side projects.

For example, in June 2019, we encountered many problems related to data quality. The founder of CHD then took the risk of withdrawing from several projects such as selling to international accounts, creating new products, or establishing strategic partnerships. With the extra time, he was able to tackle the most important issue head-on. In the scenario above, the visionary here had the courage to take off his booster, builder, and ambassador caps to focus momentarily on the Chief Expert profile. For one quarter, he isolated himself in order to draw up an action plan that would allow us to retain our long-standing clients. The strategy is paying off.

Essential Cohesion

These profiles only make sense if they form a cohesive group. Just as in sports the mere addition of individual superstars doesn’t necessarily improve the quality of the team, scaling up requires strong team spirit. This brings us back to the root of the word company, cum pane, evoking the idea of people with (cum) whom we break bread (pane). If you are responsible for building such a team, keep in mind that certain values will be essential to guarantee its performance.

— Lionel Benizri —